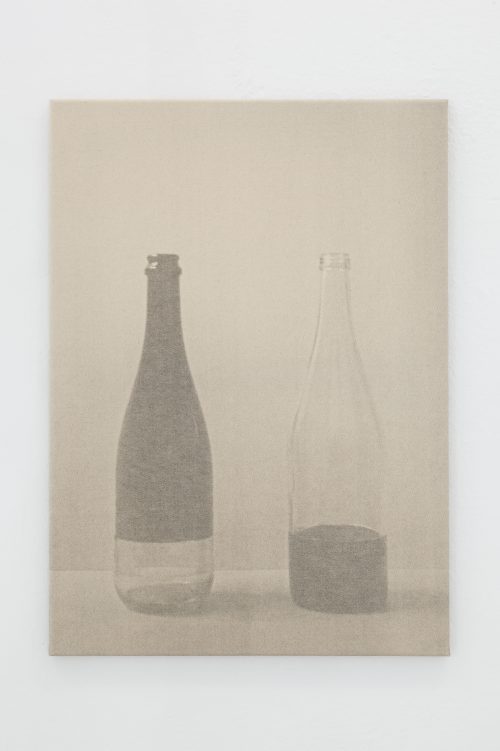

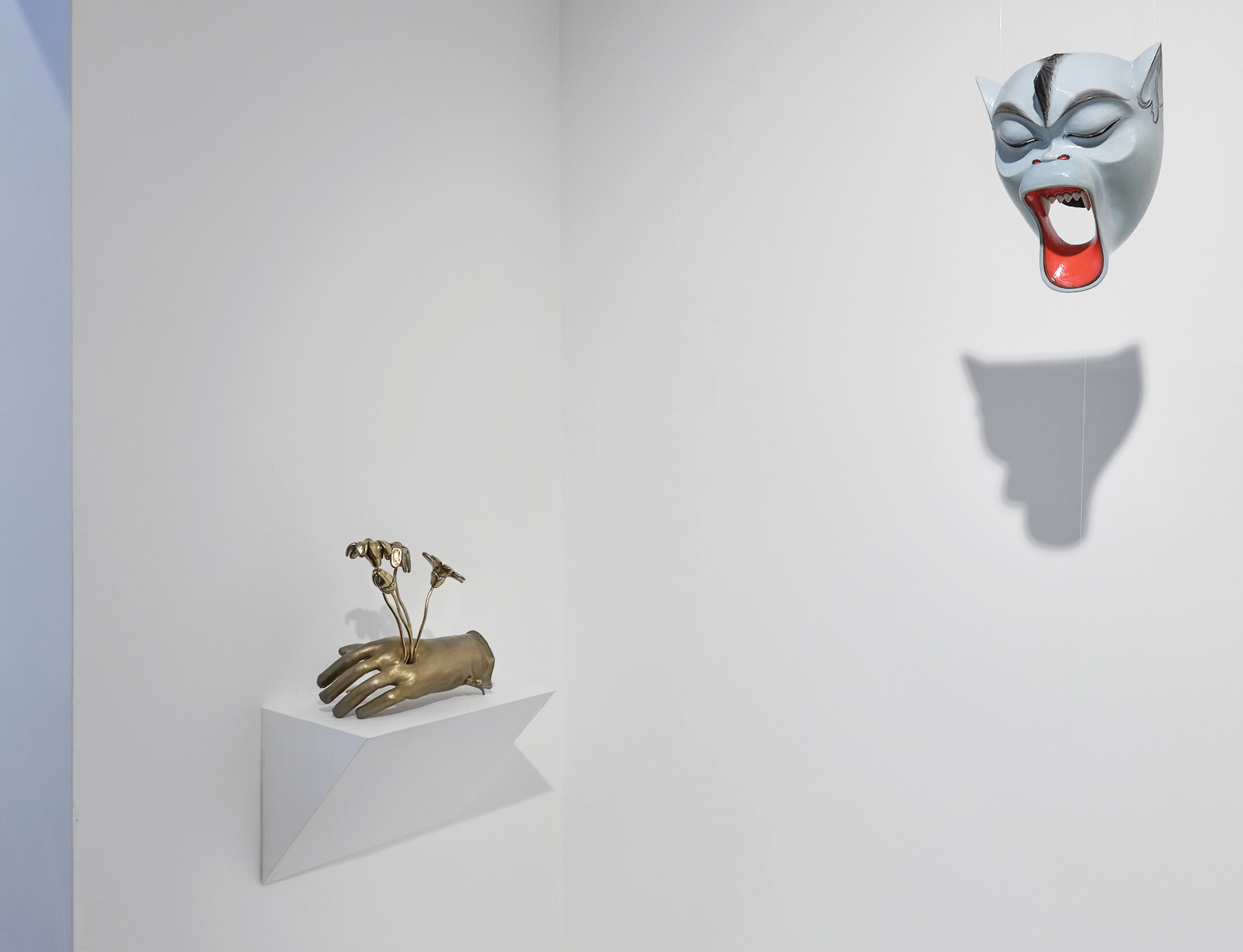

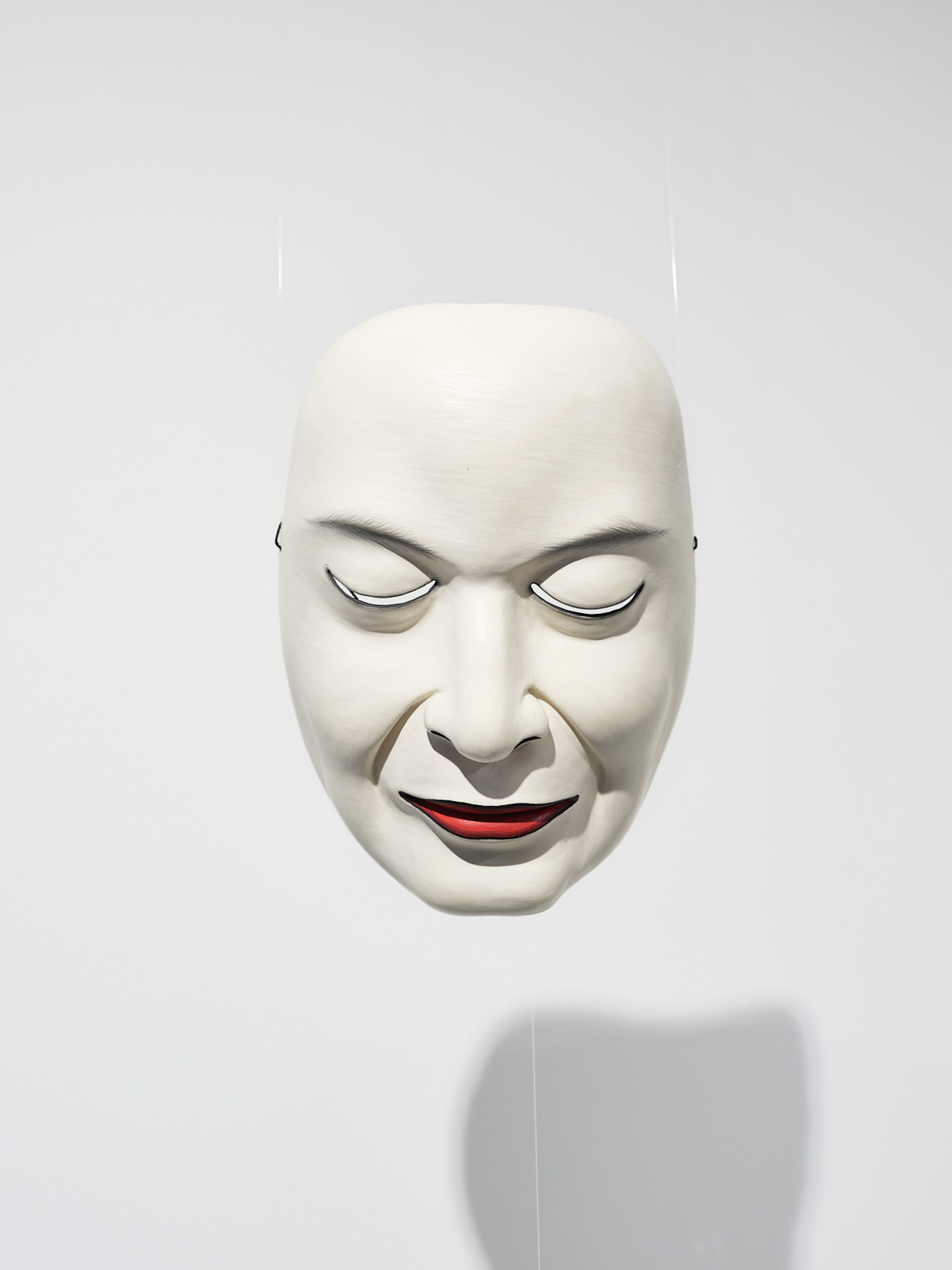

Alexandra Barth, Maurizio Vetrugno, Rose Nestler, Weinbenami

"Bella Figura"

Project Info

- 💙 Carole Lambert Presente

- 💚 Raphael Giannesini

- 🖤 Alexandra Barth, Maurizio Vetrugno, Rose Nestler, Weinbenami

- 💛 https://www.instagram.com/objets_pointus/

Share on

Advertisement

«The Bella figura, or the art of maintaining a good appearance without ever losing face, presents itself as the title of a group exhibition in the form of a comedy of manners. Set on a theater of objects, a gathering of people converses and orchestrates appearances. Like pawns on a game board, the guests move from one subject to another: interior decoration, the precise clockwork of Swiss artisans from the Jura, table manners, the reign of Terror, and the infamous Francesco Schettino. Here it is the history of a story in search of its own morality:

« Bella figura machen, heisst der italienische Volkssport, bei dem es darum geht, andere zu beeindrucken. Auch Francesco Schettino wollte eine gute Figur machen, leider war ihm ein Felsen im Weg. »

Spiegel Online 2012

«To ‘make a good impression’ is the Italian national sport, which consists of impressing others. Francesco Schettino also wanted to make a good impression, but unfortunately, a rock got in his way.». »

Spiegel Version en Ligne, 2012

This is how the editorial of the magazine «DER SPIEGEL» presented the sinking of the Costa Concordia cruise ship near the Italian island of Giglio in January 2012. Its captain, Francesco Schettino, attempted a «sail-by salute», a forbidden and perilous maneuver involving approaching the coastline with all lights on and blaring sirens to salute its inhabitants.

When arrogance precedes the fall, they say, indignity always precedes ruin. During the maneuver, an underwater reef struck the ship’s side. Alerted by the damage, Francesco Schettino took no action other than cowardly abandoning his ship, without organizing the rescue of its 4,000 passengers. Thirty souls perished in the middle of the night. While this shipwreck was perceived in Italy as a tragedy overshadowed by shame, the Spiegel’s offensive remark was seen by Rome as a national insult.

Amidst the Eurobond crisis, behind the «Bella Figura», the editorial actually seeks to draw a comparison between Schettino’s attitude and that of the entire Italy facing its debt. By extension, but mostly by shortcuts, Italy is once again chastised for its taste for excess and propensity for fleeing. But is it really failing its obligations? With a debt totaling 1,605 billion euros, more than its national wealth, this debt, inherited and passed from generation to generation, seems out of control to this day. After Greece, Italy now finds itself at the mercy of usurers.

Its landscape, vineyards, and cypresses, its art, its language, and its memory are entirely surrendered to hydraulic finance. Political power has been transferred to rating agencies and central bank governors. And its prime minister, a mere puppet manager, looks the other way. A great lover of lavish parties, Silvio Berlusconi, a man of spectacle, with his predatory smile, lying mouth, and tailor-made Caraceni suits, doesn’t even know how to save face anymore. The Colosseum is up for sale.

Following economic law, «La Bella Figura» becomes a new motto signifying living on credit! With the only lever of growth being an aesthetic of expenditure, Italy cuts a sorry figure when its capitals turn around. To finance its way of life, the country only knows demand-led recovery, i.e., recovery through borrowing, a form of financial juggling where the debt - or rather its interests - are repaid only by contracting another debt. «Dolce Vita» shines, consumes, and consumes itself; it conceals reality in favor of artifice, through style, through play, through seduction, it seeks its truth in a lie that seems acceptable.

Perhaps one must read Goethe and his grand tour, from Lake Garda to Sicily, to understand how advocates of rigor have always judged the presumed Italian carelessness: They fantasize about it, envy it, fear it. For them, what separates the ant from the grasshopper, the useful from the pleasant, separates Germany from Italy, one prepares, the other parades. The grand economic and monetary union tries through reason to reunite what Luther and Calvin sought to divide through their faith. Despite the Schengen area, the old quarrels of the atomized churches replay between the north and the south in the crisis.

Protestantism is based on limiting enjoyment, elevated as a virtue. If for Loos, ornamentation is a crime, for Protestant morality, debt is a fault. It’s the well-known rule of «Less is more»! This asceticism, based on economic rationalism and individual responsibility, frugality, and savings, contradicts the very idea of detachment, or even worse, of «far niente» (idleness). Feeling bound to Italy, like a body to its spirit, it refuses to abandon it. Empires are born in discipline and die from their culture; through boredom, loneliness, art, and wealth, they withdraw into themselves to only appear in an aesthetic of indifference leading to the indifference of their own shipwreck. Perhaps when the end comes, forgiveness comes too?